01:12

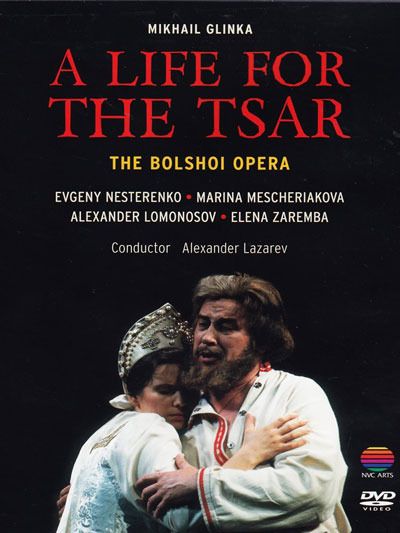

Life For The Tsar (Bolshoi Opera) / Glinka, Nesterenko, Zaremba, Lazarev [DVD]

Posted by Allegretto

Life For The Tsar (Bolshoi Opera) / Glinka, Nesterenko, Zaremba, Lazarev [DVD]

Conductor: Alexander Lazarev | Composer(s): Mikhail Glinka | Director: Nicolai Kuznetsov | Performer(s): Boris Bezhko, Marina Mescheriakova, Yevgeny Nesterenko, Elena Zaremba | Orchestra/Ensemble: Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, Bolshoi Theatre Chorus | Label: Kultur Video | DVD | Picture format: 16:9 | Sound format: Dolby Digital 2.0 | File host: Share-online.biz | 5% recovery record + 1 .rev file | Run time: 175 minutes | 8.73 GB Language(s): Russian | Subtitle(s): English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish

Conductor: Alexander Lazarev | Composer(s): Mikhail Glinka | Director: Nicolai Kuznetsov | Performer(s): Boris Bezhko, Marina Mescheriakova, Yevgeny Nesterenko, Elena Zaremba | Orchestra/Ensemble: Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, Bolshoi Theatre Chorus | Label: Kultur Video | DVD | Picture format: 16:9 | Sound format: Dolby Digital 2.0 | File host: Share-online.biz | 5% recovery record + 1 .rev file | Run time: 175 minutes | 8.73 GB Language(s): Russian | Subtitle(s): English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish

A Life for the Tsar is a "patriotic-heroic tragic opera" in four acts with an epilogue by Mikhail Glinka. The original Russian libretto, based on historical events, was written by Nestor Kukolnik, Baron Egor Fyodorovich (von) Rozen, Vladimir Sollogub and Vasily Zhukovsky. It premiered on 27 November 1836 OS (9 December NS) at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in St. Petersburg. The historical basis of the plot involves Ivan Susanin, a patriotic hero of the early 17th century who gave his life in the expulsion of the invading Polish army for the newly elected Tsar Mikhail, the first of the Romanov dynasty, elected in 1613.

Watch a Trailer (sample is a lower resolution than actual DVD or Blu-ray):

REVIEW:

Göran Forsling, MusicWeb-International

Mikhail Glinka is generally regarded as the founder of the Russian nationalist school of opera. That said, the musical language of this, his first opera, is influenced by the contemporaneous Italian style; Glinka met both Bellini and Donizetti in Milan. The story is firmly based in Russian history, in this case the Polish attack on Russia in 1613 upon the death of Boris Godunov. The peasant Ivan Susanin’s daughter, Antonida, is in love with Sobinin but the father will not allow them to be married until a new Tsar is elected. Sobinin reports that a new Tsar, the young Mikhail Romanov, has already been chosen. He is kept in a monastery and soon Polish forces arrive and Susanin has to show them the way to the monastery. Before he leaves he tells his adopted son, Vanja, to ride to the monastery and warn them, while he leads the Poles astray. When they realise that he has fooled them they kill him, but the Tsar is saved and Ivan Susanin becomes a national hero. After the Russian revolution this plot was not feasible and had to be changed so that Susanin delivered Russia – the title was also changed to Ivan Susanin – when the opera was mounted at the Bolshoi in 1939. A recording of this version from the late 1940s exists (Naxos 8.111078-80 - see review). When the communist regime collapsed in 1989 the original libretto was reinstated and the present production from 1992 is based on it. Even though Glinka’s initial thoughts were to have the opera named Ivan Susanin, it was first performed under the title A Life for the Tsar and also dedicated to the Tsar.

This production is traditional with period costumes and colourful realistic sets in the mode of 19th century paintings or – in the act III finale – expressionistic à la Munch with dark-and-red clouds drifting by in the background. Act IV is divided in three tableaux following each other without interval. The first, with Sobinin and his soldiers in the winter landscape, has frosty blue scenery. During Susanin’s final monologue, filled with reminiscences of the vanished happy family life, there are also visual flash-backs in the shape of stills from the preceding acts. Although filmed at the Bolshoi this is obviously not a public performance: there are no signs of an audience, no applause – acts tends to end in no-man’s-land, faded out.

Typical for the Russian national opera is the central part of the people and this work is no exception. The chorus has a lot to do in different guises: as wedding guests, as soldiers, as ordinary people. The vast Bolshoi stage is more often than not crowded – swarming but well organised and not always so thrilling. The singing is good, as is to be expected from these forces. The male chorus at the opening of act I sounds very much like the Don Cossacks. There is a lot of impact in the concerted choral scenes, in spite of some strident sopranos that become unduly exposed. Not least the contrapuntal conclusion of act III is powerfully dramatic. The famous Bolshoi ballet also has a lot to do, especially in the second act, playing at the Polish head-quarters, which is mainly a series of festive parades, choruses and dances. It is of course a treat for the eye and the ear and one cannot but admire Glinka’s light and translucent scoring. For repeated viewing though – when I want to follow the unfolding of the drama – I may sometimes choose to skip the ballet and go directly to the finale where, within five minutes, the dramatic reason for the whole act is concentrated: a messenger arrives and tells the people of the Polish defeat and the election of the new Tsar and they decide to find the monastery where he is hiding. Presiding over the whole of it is Alexander Lazarev, whom I have had reason to praise on several occasions. He seems to have an unerring sense of the right tempo and his watchful eye never misses an entrance, as can be seen during the entr’actes, which are fine little symphonic poems, setting the mood for each scene.

We are fortunate to have four splendid artists in the main roles and at the centre of the proceedings is the great Evgeny Nesterenko as Ivan Susanin, a dream role for a sonorous bass. And sonorous he certainly is, his large voice in mint condition down to the blackest low notes. But it is his identification and involvement in the role and his commanding stage presence that impresses most of all. His physical grandeur is of course a great help – he never has to struggle to be seen, even when the stage is flowing over with people. Even more striking is his acting with small means, his facial expression, his eyes and his ‘silent’ taking part in the action even when he is not singing. Like his Boris Godunov which I reviewed not long ago he creeps under the skin of his character and his pithy, sensitive singing – off the text – can be revelled in. Just try his duet with Vanja in act II (Ch. 11) and of course his great monologue in act IV (Chs. 19, 20).

But he is not alone in vocal splendour. The young Marina Mescheriakova as his daughter Antonida cuts a lovely portrait – she is a lively actor too. In spite of some East-European hardness and stridency to the tone at forte - today she has mellowed - she has excellent pianissimos. A certain hardness is also characteristic of Alexander Lomonosov’s fearless tenor. Sobinin is a notoriously taxing role with its high tessitura, requiring the singer to hit six high Cs and – as if this weren’t enough – two D-flats! The aria was famously recorded by the Danish tenor Helge Rosvaenge in 1940, shortly after the premiere of A Life for the Tsar at the Berlin State Opera. It is included in the appendix to the Naxos set, mentioned above, but Lomonosov is more reminiscent of Nicolai Gedda, both the actual sound and his looks. He isn’t free from strain and one or two top notes are pinched but he radiates charm. While lacking the last ounce of the warmth that should also be in this character, his is a winning performance.

The most impressive singing – besides Nesterenko – comes from Elena Zaremba. She looks young – even in close-ups, and the producer obviously fell in love with her expressive and charming face – but she was no real newcomer to the stage. Her Bolshoi debut took place a full eight years earlier. Her voice is a true contralto with booming – no, I am not exaggerating – low notes of the kind that send shivers down the spine just as much as a high soprano’s top. It is beautiful, clean, expressive and personal. Her great aria outside the monastery in act IV is magnificent.

The production as such is hardly innovative - which in today’s terms more often than not implies transporting the action to modern times or being performed in a Zen inspired body-language - but it is an honest recreation of a chapter in Russia’s blood-stained history. For that, for much wonderful music expertly performed by Lazarev and his forces and for inspired and excellent singing and acting from the four main characters this is a worthy addition to the growing catalogue of DVD operas.

Works on This Recording

A Life for the Tsar by Mikhail Glinka

Performer: Boris Bezhko (Bass), Marina Mescheriakova (Soprano), Yevgeny Nesterenko (Bass), Elena Zaremba (Alto)

Conductor: Alexander Lazarev

Orchestra/Ensemble: Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, Bolshoi Theatre Chorus

Period: Romantic

Written: 1834-1836; Russia

1 comments:

Thank you

Post a Comment